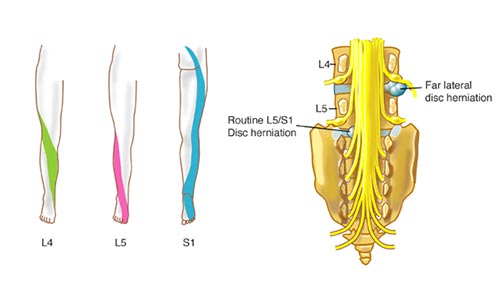

Back pain comes in all shapes and sizes and sometimes difficult to pinpoint the precise source of pain. Sciatica has a more distinct pattern of pain and is defined as pain associated with the sciatic nerve, which can run from the lower back, into the buttocks and down the legs to the feet (it’s the longest nerve in the body). Characteristically, sciatica involves radiating leg pain that follows a dermatomal pattern along the distribution of the sciatic nerve. The most common sciatic nerve referral pattern is the Lumbar nerve root 4 and 5 (L4/L5) and Sacral nerve root 1 (S1) – see Figure 1.

The pain caused by sciatica can range from being mild to being very severe and can occur suddenly or come on gradually. Sciatica maybe accompanied by numbness, pins and needles or, in more severe cases, actual weakness affecting the ankle or toes.

Sometimes sciatica is caused in the low back, commonly referred to as a herniated disc (sometimes called slipped disc or radiculopathy). However, there can be many changes to the lumbar disc and common lumbar disc pathology is characterised as degenerative and/or traumatic disc changes, including an annular tear, herniation and degeneration. Less common lumbar disc pathology includes serious spinal pathology and congenital or developmental variants. The term slipped disc is a poor description of the actual pathology, because our discs do not pop/slide in and out, because our spine is extremely strong and durable and designed for movement. Pressure on the sciatic nerve as it descends through the tissues of the buttock and leg may cause sciatica e.g. muscles along its path, sometimes due to lack of movement or too much repetitive movement. Commonly, this occurs at the buttock region (sometimes described as piriformis syndrome).

In most cases, sciatica settles within normal time frames of 6-12 weeks with conservative management, in the absence of suspected serious spinal pathology. However, for recalcitrant sciatica an MRI is the most common investigation of choice. In most cases, the MRI report will include several anomalies. However, the key to the MRI report is correlating the clinical picture i.e. patient’s pain distribution with the MRI findings. For example, if a patient is suffering with L5 nerve root pain, as illustrated above, does the MRI demonstrate any significant nerve compression on the L5 nerve root? If there is significant nerve compression then a spinal surgeon opinion is required for appropriate management. However, in most cases the MRI offers reassurances that there is no significant nerve compression and/or serious spinal pathology and commonly symptoms settle down with conservative management.

Figure 1. Common Sciatic Nerve Referral Pattern